Is There a Role for Offsets in Coal?

By Caroline Gentry and Mark Havel, Element Markets

Despite public declarations of net zero ambitions, developed economies are addicted to fossil fuels. While 59 gigawatts (GW) of the 212 GW coal-fired capacity in the U.S. is set to be retired by 2035, coal use has rebounded, with global demand rising to a record high in the post-COVID recovery on the heels of rising natural gas prices. Coal burn will continue to increase this year and next, according to the International Energy Agency.

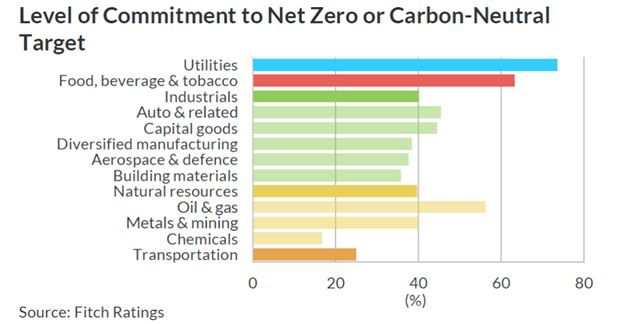

Faced with growing pressure from environmental activists and shareholders and the prospect of limited access to finance and insurance, some coal miners and consumers are seeking ways to address greenhouse gas emissions. Several international mining firms have set carbon reduction goals, including Anglo American, Rio Tinto, Glencore and BHP Billiton, and around 40 percent of metals and mining firms have set net zero or carbon neutral goals (see chart below). But many companies have found they cannot reduce emissions as quickly as they and their shareholders might like.

Hope is on the horizon, with growing support for technologies such as carbon capture and storage (CCS) and hydrogen finally providing the impetus to reach technological readiness levels. But it will still be some years before they will be implemented at sufficient scale to make a significant impact. Generators can make efficiency improvements, but beyond that, to immediately mitigate emissions from thermal fossil fuel consumption, the remaining options for coal plants are to close or buy carbon offsets. Simply switching off coal is not an option for many states which rely on them for reliable base load power.

The link between economic activity and emissions is still inextricable, says Frank Maisano of Bracewell LLP, a Washington, DC law firm. “As we come out of COVID, we’re in the middle of an oil and gas boom, that’s driving prices up. Offsets allow us another tool to understand the energy reality. They are a short-term bridge to get to CCS viability, to get to hydrogen that will really reduce emissions, giving us the flexibility to meet those challenges in an affordable and reliable way.”

The integrity of projects to generate offsets has been called into question by some environmental groups, who say they allow polluters to buy their way out of actually cutting emissions, and that many of the projects awarded credits would have happened anyway and so do not achieve real reductions. Overreliance on offsets at the expense of meaningful low-carbon investments could expose buyers to long-term regulatory and reputational risks, says David McNeil at ratings agency Sustainable Fitch.

Level of Commitment to Net Zero Carbon-Neutral Target

Cut First, Then Offset

The first step should always be to reduce emissions where possible, and offset only what cannot be avoided.

“Carbon offsets are not intended to be a device for letting companies off the hook but rather should be used to complement direct reduction activities companies are undertaking,” says John McDougal, vice president of Environmental Products at Element Markets, an asset management firm which partners with companies to create smart sustainability and compliance solutions. Companies pursuing voluntary greenhouse gas reductions should follow a three-step process:

- Quantify Scope 1-3 emissions.

(1 = direct, 2 = indirect from power consumption, 3 = indirect from use of products sold) - Identify and implement all opportunities for emission reductions within the company’s current operations, owned or controlled sources and third parties.

- Use carbon offsets to address any remaining emissions that cannot otherwise be reduced or eliminated.

Global mining firm BHP Billiton has used offsets from avoided deforestation in Peru and Kenya as a complementary measure to its ongoing climate mitigation efforts. “Although we prioritize our internal emission reduction projects, we acknowledge a role for high-quality offsets in a temporary or transitional capacity while abatement options are being studied, as well as for ‘hard to abate’ emissions with limited or no current technological solutions,” the company says on its website. But it also says that it does not intend to rely on offsetting as a matter of course, and only considers offsets a short-term low-cost abatement option.

All carbon offsets that Element Markets transacts represent greenhouse gas reductions or removals that have been independently verified by an accredited third-party auditor and are registered by a non-profit registry. For voluntary carbon offsets to qualify for registration, they must meet five key criteria: permanent, additional, verifiable, enforceable and real.

Much progress has been made in recent years, with greater transparency and standardization creating more confidence in the market. Offsets are gaining credibility as several robust standards are now well-established and measurement technology for verification purposes has advanced.

Four leading standards and registries have emerged in the voluntary market, tracking and certifying offsets from carbon capture, storage and use, forestry, methane destruction, energy efficiency and industrial processes. They are the American Carbon Registry (ACR), the Climate Action Reserve (CAR), the Gold Standard and Verra, formerly the Verified Carbon Standard (VCS).

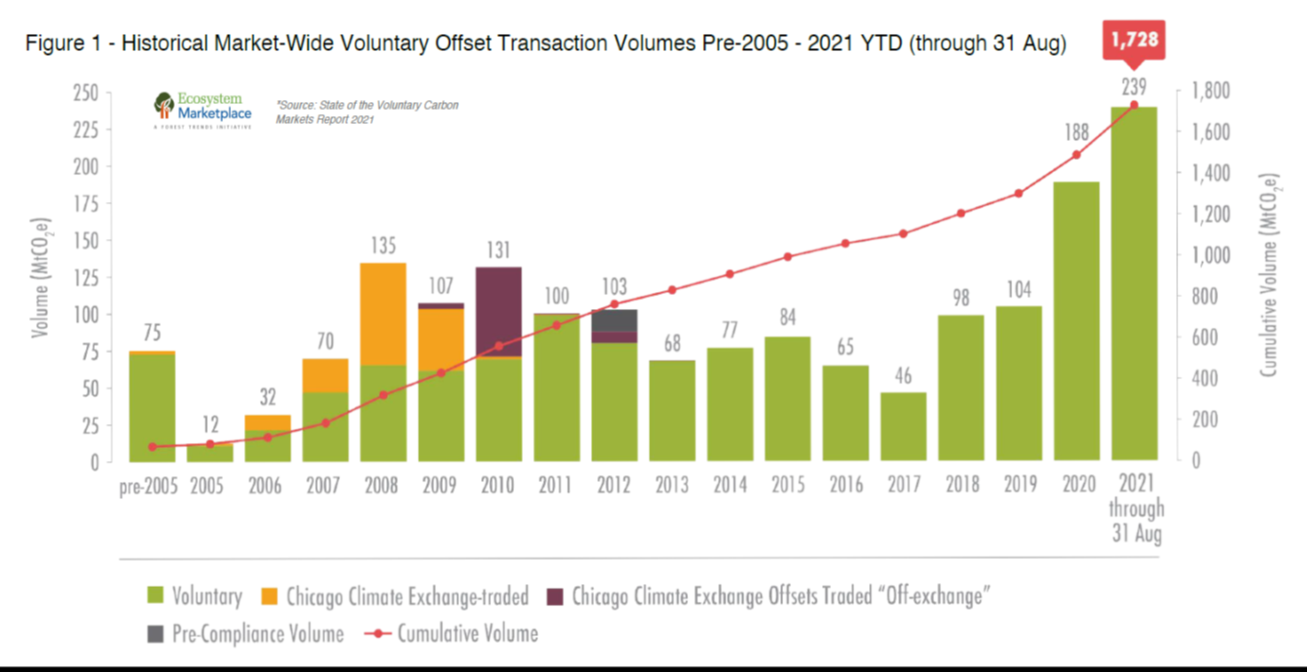

Further standardization will help to scale up voluntary carbon markets. An initiative called The Taskforce on Scaling Voluntary Carbon Markets (TSVCM) launched in September 2020 by former Bank of England Governor Mark Carney aims to create a liquid, transparent market. More than $1 billion of voluntary carbon was traded on and off exchange globally in 2021, according to Ecosystem Marketplace, and McKinsey estimates that the market for carbon credits could be worth more than $50 billion by 2030.

Demand for credits from nature-based solutions such as sustainably managing at-risk forests, grasslands and other ecosystems continues to be strong, which will push prices higher. The weighted average price per tonne was $4.73/tonne in 2021 according to Ecosystem Marketplace, but some offsets associated with activities that remove carbon from the atmosphere rather than an avoidance of GHG emissions can sell for more than $100/tonne. A two-tier system of avoidance and removal offsets is beginning to emerge. Prices for renewable energy credits were around $1 in 2021, reflecting the fact that the financial additionality case is harder to make for renewables as they become increasingly competitive with fossil-based energy. Some registries have updated their policies to exclude large-scale grid-connected renewables.

Critics sometimes point to this lack of “additionality”, or reductions that would have happened under common practice or business-as-usual, as a reason to discredit all offsets.

But in doing so, they are potentially jeopardizing the opportunity for real emission reductions that genuine carbon abatement projects can deliver.

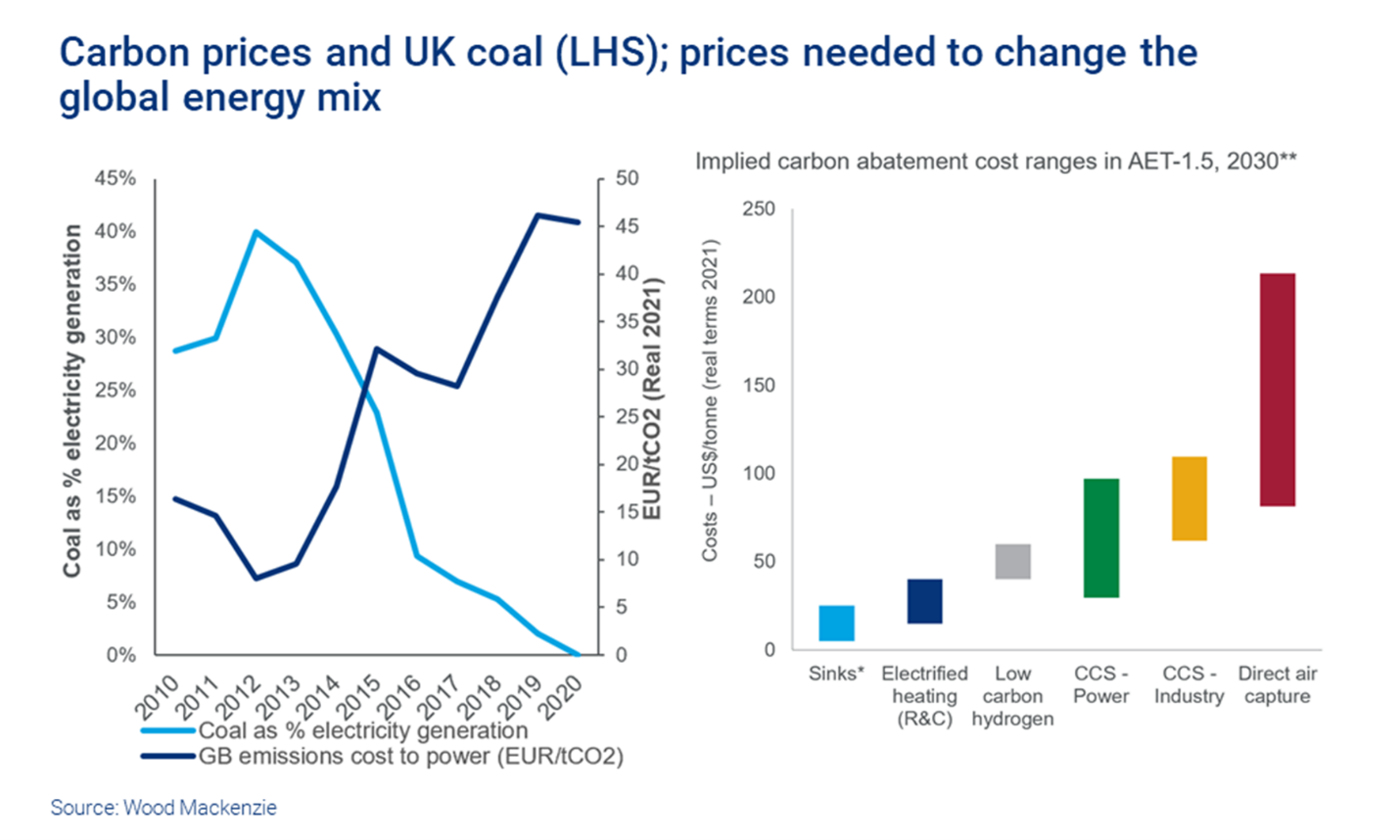

The average price of an offset is not yet high enough to change the order of the generation stack. Carbon prices of at least $30/tonne are needed to change the global energy mix, according to Wood Mackenzie, as shown in the graphic on the next page.

In the U.S. offsets are unlikely to move the needle much for keeping coal plants operational, which is a political decision, says Ian Lange, director of the Mineral Energy Economics program at the Colorado School of Mines. So even adding a high carbon penalty will not make a difference if taxpayers are forced to prop up uneconomic units, or if the Environmental Protection Agency enforces regulations necessitating early retirement. In Colorado, Oregon and Washington, regulators are forcing plants to close, while in Indiana and Montana, legislators are trying to keep them open. Those who worry about pollution will only see offsets as “putting a Band-Aid on a massive wound,” Lange says. But if the money is spent on emission reduction projects or easing the burden on consumers who are paying for them, it may appease the critics where there is no short-term alternative to coal.

Even if the political will is there to support coal, lending institutions and investors including JP Morgan Chase, Bank of America and BlackRock are increasingly pressured to shift investments away from higher emitting sectors.

“As an investor, I would only invest in a coal company with a credible transition plan or a capital repayment wind-down program consistent with 50 percent reduction in emission by 2030 and 0 percent by 2050,” one sustainable finance investor said.

An Opportunity, Rather Than a Cost

Rather than a cost burden, the environmental markets can be a source of income for coal companies. Coal mine methane capture projects can generate offsets for use in California’s compliance program as well as the voluntary market, and if the gas is used to generate electricity, it is awarded a renewable energy certificate in some states that can be used for compliance with renewable energy mandates. Even waste coal is classified as an alternative energy source generating credits in Pennsylvania, reflecting the positive environmental benefit of cleaning up waste coal piles. So it is likely to be in finding ways to sell environmental credits rather than buying them that will allow coal plants to remain operational for longer, and creating revenues to plow back into CCS or renewables with batteries.

Potential project developers must ensure they understand the details of the various methodologies – just because it reduces emissions, a project does not automatically qualify for an offset. For example, coal mine methane projects injecting the gas into a pipeline are highly effective, but do not generate offsets in California’s cap-and-trade program, as the regulator considers them business-as-usual.

Credible offsets represent a useful flexibility option in the fossil fuel industry’s toolkit as the energy sector pursues decarbonization. A one-size-fits-all approach will not work to deliver a just transition as some hard-to-abate sectors or regions without access to renewable resources will be more heavily penalized, with potentially very high costs being passed through to consumers. Coal companies should not be accused of greenwashing if they support genuine emission reduction projects and use offsets as a way to fulfill environmental goals.

Caroline Gentry is director environmental products and Mark Havel is environmental products analyst at Element Markets