Crisis in the Resource Industry: America’s Shortage of Mining Engineers

By David L. Kanagy, Society for Mining, Metallurgy, and Exploration, Inc.

Like many university-level STEM (science, technology, engineering, math) programs, mining schools are finding it difficult to recruit students to pursue a mining engineering degree and then to further encourage them to seek a career in the industry. Many complex challenges are associated with the recruitment of students and with encouraging young professionals to select a career in the mining industry. However, with the collaboration of a diverse group of organizations and individuals, this challenge to the health of the mining industry can be vastly improved. The Society for Mining, Metallurgy, and Exploration (SME) is working to find solutions and support our mining and metallurgical school programs.

The mining industry depends upon a workforce trained at the university level in mining, metallurgical and geologic engineering programs, and related disciplines essential to the operation of mines and processing mills. Without these degreed professionals, the nation’s mines could face safety and environmental challenges that would slow the production of minerals needed for our modern economy. A skilled workforce is essential to ensuring production of the raw materials and critical minerals necessary for our economic and national security, the restoration of aging infrastructure and for the transition to a clean energy future A well-trained workforce is essential to coal production. Coal is not only thesource of 36 percent of all electricity generated worldwide, but it also is important in the production of steel, cement and carbon foam products. Research is also underway to explore the extraction of rare earth minerals from coal deposits.

Electric vehicles alone will require a massive increase in copper production from 174,000 tons in 2017 to 1.75 million in 2027, according to the National Mining Association and SME technical briefing papers.

Engineering programs suffer from declining investments and research and development (R&D) funding. The latter has contributed to a decline in faculty, enrollment and graduation rates. SME tracks these trends related to U.S. schools and has found that the U.S. situation differs from other parts of the world but is similar to developed nations such as Canada, Australia, the United Kingdom and other areas. And, though SME has 85 student chapters, only 22 are in the United States.

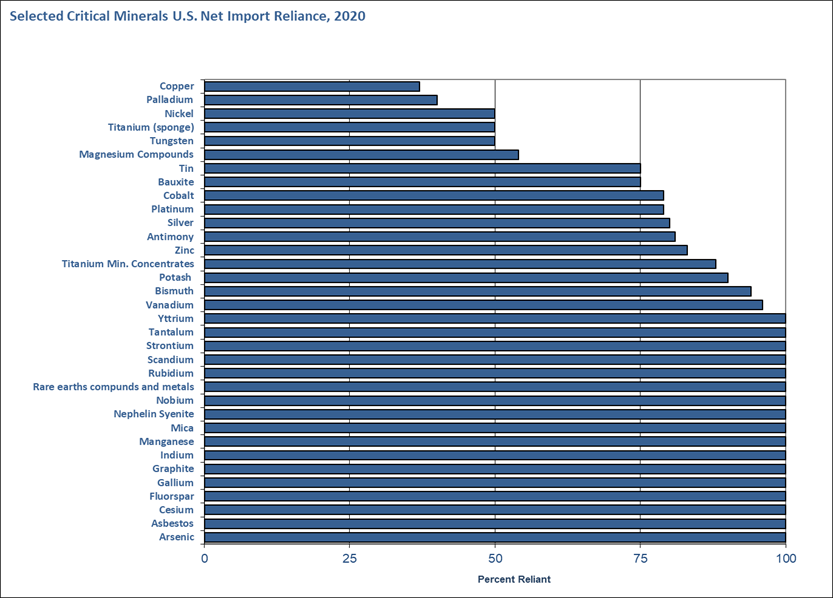

This shortage of a qualified workforce threatens to increase U.S. reliance on imports of raw materials and critical minerals from other countries, specifically those mined in geopolitically unstable regions or in countries whose interests are averse to the U.S.

A shortage of talent will hinder the extraction of minerals needed for the transition to non-carbon solutions and the manufacture of batteries, electric vehicles and other green economy products. The U.S. is more than 50 percent dependent on imports of 31 of 35 critical minerals needed for our clean energy future, according to the U.S. Geological Survey, as shown in the chart below.

Figure 1: Mining Engineering

The process of accreditation of mining, metallurgical and geological engineering schools is rigorous. SME is responsible for this through the Accreditation Board for Engineering and Technology (ABET). SME provides the peer review evaluators and assigns them to various schools for these reviews based on the established criteria. These evaluators review the seven criteria detailed in the APPM, which include evaluation of students, program educational objectives, student outcomes, continuous improvement, curriculum, faculty, facilities and institutional support.

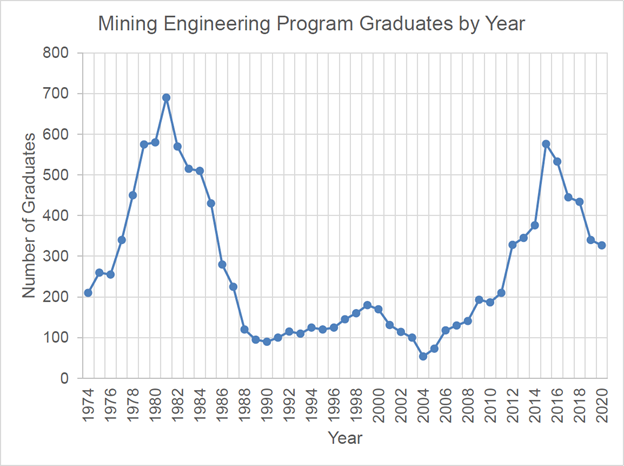

SME has also worked to provide funding for mineral education. Since 2015, the Ph.D. Fellowship and Career Development Grant Program created by SME and the SME Foundation has supported the development of those who choose an industry-related academic career. This program awarded four-year fellowships to 22 individuals worth a total $240,000 to each recipient to earn a Ph.D. and become qualified for a faculty position. In total, SME has awarded $5,280,000. Over three years, the program also granted $300,000 to 14 young professors to obtain tenure at their university. This totals more than $8 million SME has invested in our profession to ensure the next generation of talent and expertise. However, mining school enrollment and graduation rates are declining, as the chart below demonstrates.

Figure 2 shows a general decrease in the number of mining engineering program graduates since the early 1980s peak. Since 2015, the number of graduates has decreased by about 43 percent.

There has also been a steady decline in the number of mining and mineral engineering programs at U.S. colleges and universities from a high of 25 in 1982 to 14 today. This corresponds with a decline in U.S. faculty, to about 112 in mining engineering in 2020. This includes instructors and professors of practice (who generally do not require a Ph.D.) as well as a shortage of qualified candidates to fill these vacancies.

Mining will add jobs at a fairly constant rate (11,000 to 13,000 per year) over the next 20 years, driven by retirement of the current workforce and projected increase in demand for resource production. These tend to be well-paying, relatively long-term jobs. On the downside, the U.S. may not have the skilled labor or educational base to meet the current resource demand, and the skilled labor that does exist may well be lured to places promising higher wages (Australia, Canada, etc.).

Federal funding of studies and research in mining has been drastically reduced and the dissolution of the former federal Bureau of Mines removed all funding for mining schools under the Mining and Mineral Resource Institutes Act of 1984. While there has been a noticeable increase in the number of graduates from mining and mineral engineering programs since 2004, it is doubtful that U.S. schools, as they are currently staffed, will be able to keep up as demand for qualified graduates has outstripped supply (Fig. 2). Unless this is corrected, the nation risks losing its capacity to provide new science and engineering professionals for the mining workforce.

SME’s position on these matters is:

- The mining industry pays some of the highest wages in the U.S., according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics. This advantage over other industry wages needs to be promoted.

- Mining labor constitutes less than one quarter of 1 percent of the available U.S. workforce; yet this small workforce is the starting point for a value chain that consistently contributes 13 to 14 percent of the U.S. economy. Any loss of mining in the U.S. will result in a lower GDP from domestically mined minerals.

- Based on BLS data modeled by EIA, the U.S. mining industry is projected to grow over at least the next 10 years. In addition, industry retirements will create even more significant and immediate labor needs.

- A number of health and safety issues could likely result from this situation as younger, inexperienced employees fill open positions.

The industry has to take all steps necessary to ensure this does

not happen. Accidents will set the industry back. - The mining industry is often forced to turn to foreign schools or workers to fill the vacancies with qualified employees.

- The U.S. is obliged to preserve and foster the human capital necessary for national economic, energy and minerals security.

- Federal support for U.S. mining schools is necessary to maintain qualified faculty and an educational pipeline to supply workers to meet a growing global minerals demand.

The Mining Schools Act – Funding the Education of the Next Generation of Mining Professionals

A legislative solution to the mining education crisis may be on the way. Just this year, there has been significant movement to resolve the shortage of research dollars for U.S. schools. The Mining Schools Act (S. 3915 and H.R. 8187) directs the Secretary of the Department of Energy (DOE) to establish a competitive grant program to recruit and educate the next generation of mining engineers. The bill authorizes grants of $10 million annually for eight years to eligible mining schools. Eligible means qualifying mining, metallurgical, geological or mineral engineering programs at an ABET-accredited school and geology or engineering programs at a four-year public institution of higher education in a state where the gross domestic product in 2020 was not less than $2 billion in the combined categories of mining and support activities for mining. Schools in 24 states would be eligible to receive this funding.

The 10 grants awarded each year will be selected by a board of professionals as established by the DOE to review these proposals and select those based on merit that will support research activities for mining. The principal sponsor of the Senate bill is Senator John Barrasso (R-WY). Senate Energy Committee Chair Joe Manchin (D-WV) is a co-sponsor. Representative Burgess Owens (R-UT) sponsors the House version. Both bills enjoy bipartisan support.

Schools must use the funds for student recruitment, as well as the development and enhancement of programs related to mineral extraction, processing, reclamation technologies and protection of the environment, to name a few. Both bills await House and Senate committee hearings.

This legislation reflects the technical research and work of SME’s Government and Public Affairs Committee (GPAC). Responding to a request for technical support from Senate Energy & Natural Resources Committee staff, the GPAC submitted a paper entitled “Maintaining the Viability of U.S. Mining Education,” which highlighted the critical need to fund the education and training of the future mining workforce.

SME’s GPAC has also published several related technical briefing papers on U.S. import dependence on critical and rare earth minerals, and how delays in obtaining mine permits hinder the development of minerals essential to our nation’s economic and social well-being. GPAC papers are designed to provide lawmakers, regulators and the public with information about mining-related topics.

The stakes are enormous. By not addressing these shortages adequately and with haste, we jeopardize the ability for mining to be maintained in the U.S. as well as other parts of the world. Without mining, there is no successful transition to clean energy. The resolution of this crisis will require the dedication, cooperation and support of the public and private sectors.

David L. Kanagy, CAE, is executive director and CEO of the Society for Mining, Metallurgy, and Exploration, Inc. in Englewood, CO.